The acetate base of this negative has shrunk, creating bunching or channeling of the gelatin layer and distortion of the image. Often both base and emulsion sides of the film will be affected by delamination, as seen here. This is because the base side of many films have been coated with a gelatin anti-curl layer that is as susceptible to channeling as the binder containing the image. Plasticizer exudation can also be seen on the emulsion side of this negative (left).

This acetate negative, viewed from the base side, shows large channels of the gelatin backing layer have separated from the film support.

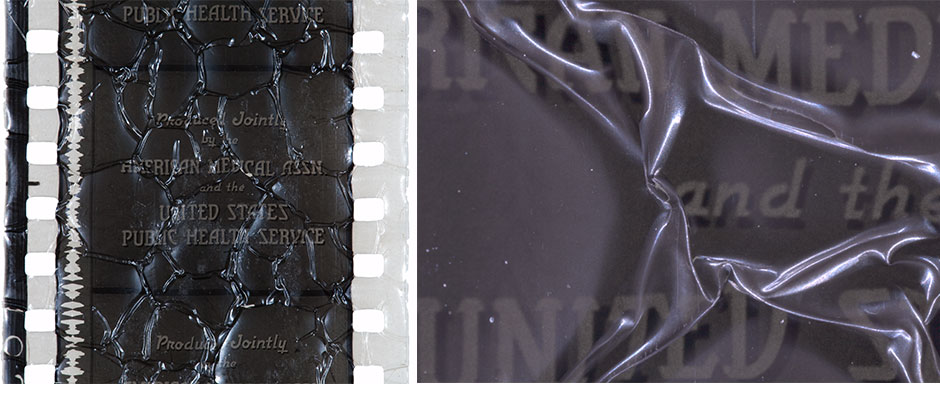

(Left) This acetate 35mm, viewed emulsion-side up, has bunched and formed the channels more typically seen in sheet film. (Right) This detail of the previous image shows the permanent channeling of the gelatin binder layer.

What it is and what causes itWhen acetate film decays, acetic acid is released from the film support. The free acetic acid promotes chain scission, the shortening of the long polymer chains that comprise the acetate base. When these polymer chains shorten, the base shrinks, and shrinkage can cause the gelatin binder to bunch and eventually separate from the base. Larger format films (such as sheet films) are most susceptible to delamination, but it is sometimes seen in smaller formats that are heavily shrunken.Delamination is a symptom of advanced acetate decay and can be accompanied by embrittlement and the exudation of plasticizers. |

What you can doDelamination is irreversible, but there are interventions available to preserve delaminated images from cut sheet film. Solvents may be used to soften the subbing layer and remove the gelatin layer from the support, so that the image can be flattened and transferred to a new support, rephotographed or scanned. These interventions are not risk-free and require skilled and experienced handling and considerable expense.The only way to prevent delamination is to stall the progress of acetate decay by storing film in a cold and moderately dry environment. Changes in environmental conditions may contribute to the removal of degradation by-products like acetic acid, and this in turn may contribute to delamination. Attempts to ventilate degrading film objects or remove degradation by-products lead to increased shrinkage and ultimately, delamination. For film in an advanced state of decay, freezing the film is recommended. |

At Risk

|