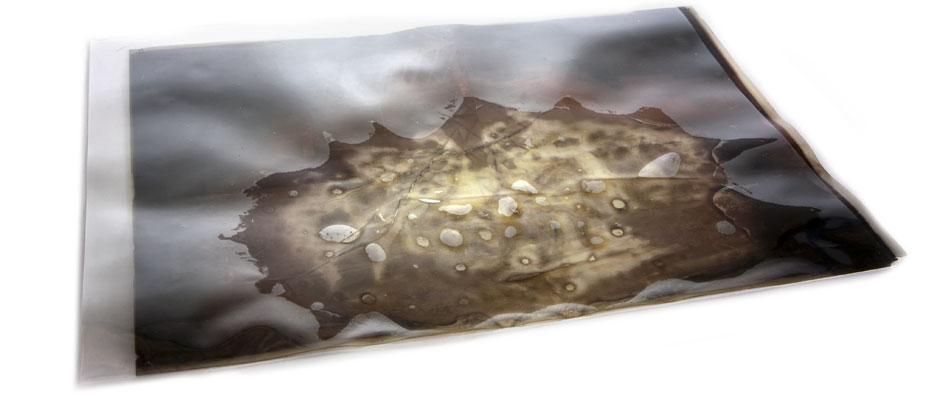

This nitrate negative enclosed in a plastic sleeve has partially adhered to the sleeve. The sticky parts of the gelatin binder are affected by near total image loss. This stickiness and softening of the gelatin is typical of the intermediate stages of nitrate decay.

In this 35mm reel of film with a yellow tint, most of the image has already faded, discolored, and the gelatin binder is bubbling and sticky to the touch. The yellow tint is now only visible on the edges of the film, where no silver image is present. This reel contains very few salvageable images.

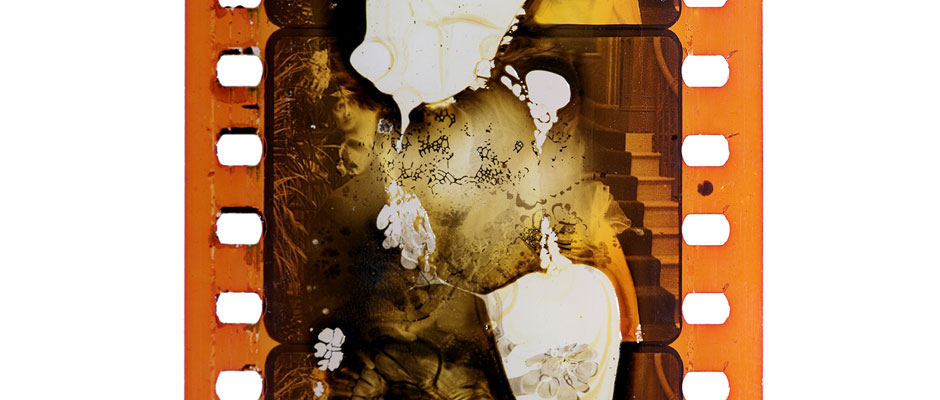

A strip of 35mm tinted nitrate film has been photographed in raking light. This view demonstrates the irregular texture of the film and sticky gelatin typical of nitrate base decay.

This frame of 35mm nitrate film is a detail of the previous image. Here, much of the image has been lost to silver oxidation promoted by nitrate decay, and the gelatin binder has become soft and sticky.

Several wraps of film taken from a 35mm tinted nitrate newsreel show varying amounts of silver fading, discoloration, and gelatin decomposition. The strip on the left shows total image loss, yellow discoloration and near total disintegration of the gelatin. Nitrate decay proceeds very rapidly, once underway.

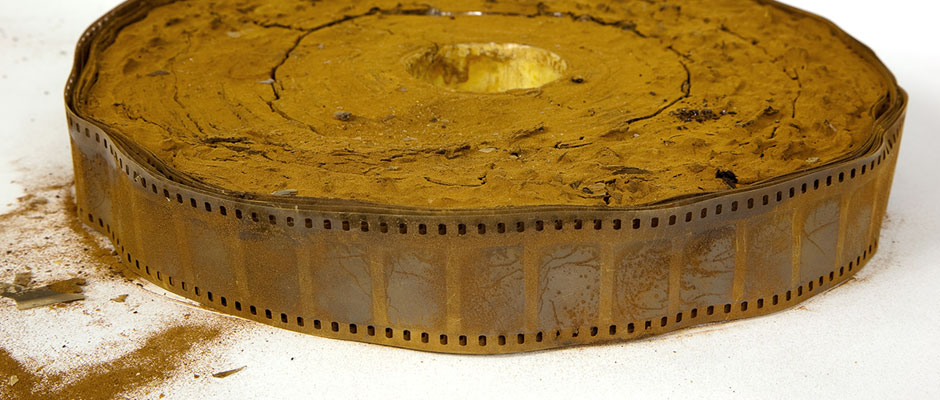

In this example of advanced nitrate decay, the remaining wraps of film have completely adhered to each other and formed a solid mass. The image contained on these convolutions of film is may not be salvageable. When handling decaying nitrate film, the use of latex or nitrile gloves is recommended.

This shows the bubbling froth present on the edges of the film pack typical of advanced nitrate decay. This sticky substance is sometimes referred to as ‘nitrate honey’.

This brightly tinted frame enlargement from a nitrate film demonstrates the familiar amber discoloration, silver fading, and sticky gelatin caused by nitrate base decay. Notice the large parts of the image that have been lost entirely.

These nitrate negatives stored in glassine have now completely adhered to each other and to the extremely brittle glassine housing.

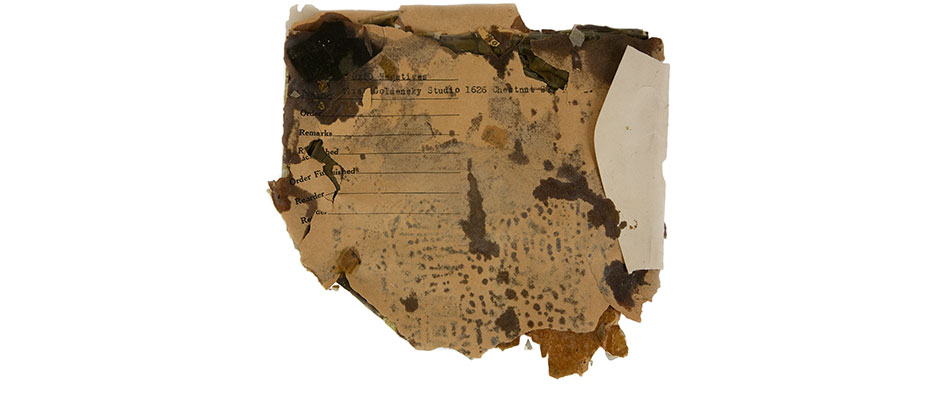

A paper envelope with an inner coating contains large format nitrate negatives. The gelatin of these negatives is so sticky that they can no longer be separated. The image on these negatives has been entirely lost to silver corrosion, and the negatives are so brittle that they cannot be handled without causing further damage. Notice the adhesion of brittle fragments of negatives to both side of the envelope and to adjacent negatives.

The nitric acid released by these decaying 8x10 nitrate negatives has discolored and embrittled the paper envelope. Any handling of the object causes irrevocable damage.

Notice here the discoloration of the envelope, a result of the attack of nitric acid on the paper, and the brittleness and adhesion of the negatives contained in the envelope, which are entirely blocked.

This roll of 35mm nitrate is coated in the familiar red/brown dust that signals advanced nitrate base decay. After the oxidizing and acidic byproducts of nitrate decay attack the silver image and decompose the gelatin, they compromise the plastic base. These oxidizing byproducts will also attack and corrode metal reels and metal cans.

This is the opposite side of the nitrate roll in the previous image. Notice how the roll is broken into three individual, solid pieces (like concentric circles). These pieces are entirely blocked, and the images on them are not salvageable.

The triacetate sleeve which housed this acetate color negative shows a brown sticky residue left by the gelatin binder. The gelatin on this negative softened when it was previously stored against a decaying nitrate negative.

In this detail of the previous image, you can see the outline of the nitrate negative which had been stored against this acetate negative. The nitrogen oxides produced by the decaying nitrate negative once stored alongside the object oxidized parts of the image and softened the emulsion in the orange area. Decaying nitrate films should not be stored with acetate films, as the strong acids and oxidizing byproducts released will also attack adjacent acetate negatives.

What it is and what causes itNitrate film is made by modifying long cellulose chains. Nitro side groups are grafted on to these cellulose chains (or polymers). Over time, as nitrate film is exposed to moisture, heat, and acids, the nitro side groups break away, producing nitrogen oxides in the film’s environment. When some nitrogen oxides react with moisture, nitric acid is produced. Nitrogen oxides and nitric acid readily promote silver corrosion, decompose gelatin emulsions, and catalyze the chemical reactions that cause further nitrate decay. Once begun, nitrate decay proceeds at an ever-increasing pace. The end result is the decomposition of the nitrate plastic itself.Gelatin softening and stickiness typically represents an intermediate phase of nitrate base decay. It is normally preceded by fading and discoloration of the image silver and followed by the decomposition of the nitrate plastic base. Nitrate decay is accompanied by an increasingly pungent, noxious odor long familiar to archivists. Decomposing gelatin may present as sticky bubbles on the surface of the film and cause negatives or wraps of film to adhere together (known as blocking). For film rolls, the blocking of convolutions of film eventually becomes irreversible, so that the film roll becomes a solid mass. This is colloquially referred to as the ‘hockey puck’ stage of nitrate decay. The last phase of nitrate decay involves the decomposition of the nitrate plastic into red/brown dust comprised of cellulose and colloidal silver. |

What you can doNitrate decay is hastened by the presence of moisture and heat, so storage of films in cold or frozen environments with a controlled, moderate relative humidity is essential. The control of temperature is the critical factor in stalling nitrate decay. Once nitrate decay begins, its progression is rapid. Nitrate film is considered a hazardous material, subject to strict guidelines for storage, handling and shipping. Nitrate film should be stored in accordance with ANSI/NFPA Standard 40 2011. |

At Risk

|